The Lowest Common Denominator Theory of The Internet

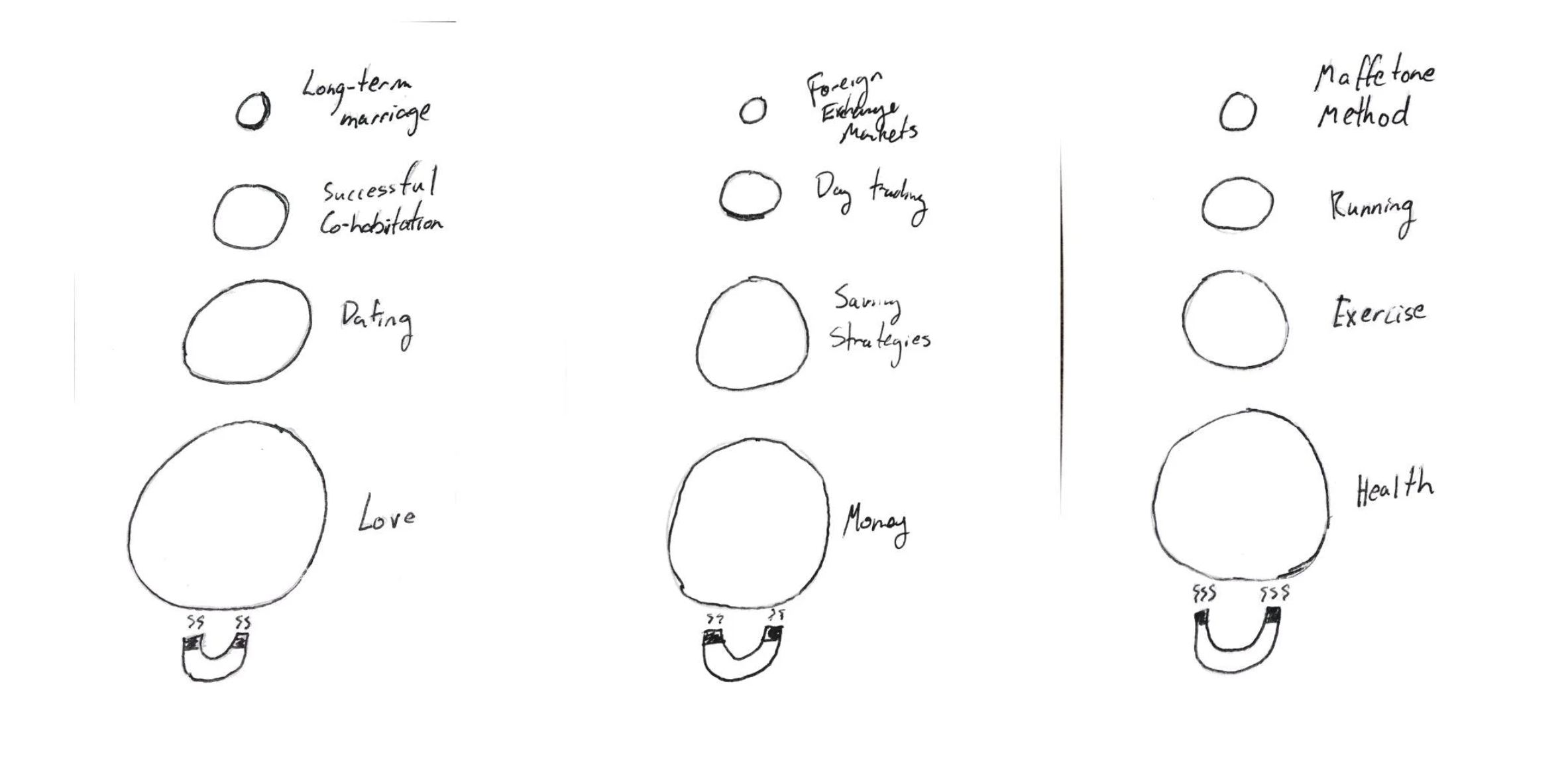

The LCD Theory of the Internet states that ambitious writers who follow the wrong metrics will find themselves writing about the most relatable content.

Money is one example of relatable content. Earning money is a fundamental, basic desire. That’s why you see a parade of blog posts talking about income. Spend a few moments on the internet, and it will appear as if people who create in the money space rise above everyone else. Money, generally, is relatable.

By definition, what is most relatable has a low degree of technical information. What is relatable DOES NOT indicate what is the most useful, or the most helpful, the most meaningful, or even the most popular.

This is a critical distinction. Web 2.0 only needs us to react, not think. To click, not consider. They want quick reactions, not deep revelations. When you see those seemingly empty low-content sound bites rise to the top, what you’re seeing is 100,000 people instantly reacting to a relatable piece of content.

Most people watch this playing out and assume society is doomed for our stupidity. That isn’t true.

People aren’t getting more shallow. We aren’t getting dumber. We aren’t becoming less attentive. We’re just connected in a way that they have never ever been before. We all see everyone reacting in real time, quantitatively. On the surface, it looks like we’re all getting stupider.

Underneath that, we’re all getting much smarter, invisibly.

These millions of connected individuals are learning more and more about what they care about. They are digging deeper. They just aren’t doing it in front of everyone. When someone learns more about supply chain operations at their job, they won’t post about that because it isn’t sexy. We’re all looking for that higher degree technical information. But, by definition, information with a high degree of technical information is less relatable.

What does all this mean for the ambitious creator?

It means that without a strong mission, the ambitious modern writer gravitates toward low-information, relatable content. People are there. Clicks are there. Money is there. All visible metrics lead to the simplest, most relatable content.

Ironically, the further you get into that specialized information, the deeper the passion. Passion is a problem for social media. Why? Because you can’t put a number on it. Still, it swims below the surface, unmentioned by anyone.

I talk with people who geek out about adjectives. If you are building a social media platform, how are you supposed to measure the degree to which a person might care about using the word “superfluous” as opposed to “extraneous?” You can’t. So you measure attention instead. Then, you call your users “creators,” make them feel special, and reward them when they meet your attention metrics.

The LCD Theory of the Internet isn’t inherently bad or evil, necessarily. It just… is. It’s a means, not an end. You have to be a very special type of person to succeed in this world for very long.

I know all of this now. I was clueless then.